As the heat over the expansion over nuclear power in Alberta seems to have cooled down a bit over the summer months, a piece in the New Scientist on the long-term consequences of nuclear left-overs caught my eye last week.

As the heat over the expansion over nuclear power in Alberta seems to have cooled down a bit over the summer months, a piece in the New Scientist on the long-term consequences of nuclear left-overs caught my eye last week.

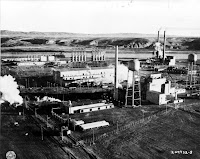

The United States Government Accountability Office has released a report raising “serious questions” about the long-term viability of the underground nuclear waste storage facility in Hanford, Washington. The Hanford Site, considered one of the most contaminated places on Earth is a decommissioned nuclear production complex on the Columbia River, built in 1943 as part of the Manhattan Project contains 210 million litres of radioactive and chemical waste stored in 177 underground tanks. With most being over 50 years old, 67 of the tanks have failed, leaking almost 4 million litres of waste into the ground in the Columbia River Basin.

At a length of over two-thousand kilometers, a basin of over 668,217 square kilometers, and a water discharge of over 7,504 cubic meters per second, the Columbia the fourth largest river in the United States and the largest river flowing into the Pacific Ocean from North America. The Columbia River Basin spreads over Idaho, Montana, Nevada, Oregon, Utah, Washington, Wyoming, and British Columbia.

Robert Alvarez, of the Institute for Policy Studies:

“The risk of catastrophic tank failure will sharply increase as each year goes by,” he says, “and one of the nation’s largest rivers, the Columbia, will be in jeopardy.”

A 2004 study conducted by Alvarez suggested that there “is a 50% chance of a major accident” while the United States attempts to clean up Hanford over the next thirty years.

Interestingly, in 2004, 69% of Washington voters approved Initiative 297 (PDF), which would halt the Federal Government’s transfer of nuclear waste to the Hanford Site until it cleaned up the present contamination there according to existing Federal and state environmental cleanup standards. Initiative 297 was overturned in 2006 by the U.S. District Court, stating that it was unconstitutional for a State to put demands on the Federal Government.

Though there is a growing need for a larger energy supply (which is increasingly unsustainable), we have a responsibility to ensure that the effects of our developments do not adversely affect the lives and well-being of the current population, as well as generations to come. As these three points frequently conflict, it is important that Albertans understand these consequences as our provincial government continues the charge towards nuclear power.